Writing begins at home

The last six weeks have made me hate where I live more than I ever could have imagined. We rent a house, a nice enough house, in Nyack, New York. After I finished the first draft of The Vapors and our family left Hot Springs to move back to New York, we knew we couldn’t return to Brooklyn. After all, we had grown from four to five, and Brooklyn just isn’t that hospitable to families of five. It’s one too many abreast on the sidewalk, one too many chairs at a restaurant table, one too many bedrooms for people who aren’t going to pay any rent. We knew we’d have to look outside of the five boroughs, and Katie made several scouting trips to New York while we were in Arkansas to find us a suitable home. She fell in love with Nyack, a village about twenty miles north of the city on the western bank of the Hudson River. I loved it, too. It seemed to be a place we’d fit in. But before we fully planted our flag there, we decided to rent a place for a year and make sure it was the right place for us. That year has now become nearly three. And the house we chose to rent, which was one of two that were available when we arrived, was a fine placeholder for us two years ago, maybe even a year ago. But after nearly two straight months of not leaving it, I find myself desperate to leave.

One of the biggest drawbacks (despite having only one bathroom, which is my own personal hell) is that the only space available for me to work is a dark room with a dropped ceiling in the basement. Over the last couple of years I have fashioned this room into something that resembles an office, a workspace, where I can disappear and try to get work done, or ride on an exercise bike and blow off some steam. More often than not, however, when I had something really important to work on, I knew better than to try to write it in the basement. I’d set out for the diner where I would chug coffee and type for hours until the wee hours of the morning. I got into this routine where I knew I would have to leave this house to get any work done. And so this wasn’t a problem, really, until I couldn’t leave the house anymore.

Being trapped inside my own home has made me think often of Laura Hillenbrand, the author of Seabiscuit and Unbroken. She wrote both of those incredible books while being trapped inside her own home. She suffers from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, which makes it not only difficult for her to travel but even to sit upright for long periods or even read books. One would think that her illness would have made it so difficult to write two densely-researched works of nonfiction, let alone write two that are essentially canonical. But Wil Hylton points out in this 2014 New York Times Magazine profile that her illness may have made her research, her reporting, and even her writing that much better. I revisited this profile as I thought of her this month as I struggled to be productive and creative while confined to my basement, and I was struck by how right that may be, and how much I took away from this piece when I first read it and used in my own research and writing of The Vapors.

Laura Hillenbrand had a lot of good tricks for doing research from home. For one thing, instead of going to libraries to read microfilm - something I had spent plenty of hours doing - she would order the actual newspapers she needed off of eBay. Then she could read them in her living room during her morning coffee as if they were the daily news. In Hylton’s profile, she says that she would read the entire paper, not just the article she was looking for, and that it would give her a better sense of the time and place, give her the context for the events in her book. I remember taking this advice, and ordering magazines and newspapers online so that I could read them this way, and transport myself into the time period. It was good advice. And just as Hillenbrand also found the idea for Unbroken while reading a random article during research for Seabiscuit in this way, I found other story ideas in the pages of these newspapers, including one I hope to write my next book about, assuming anyone ever lets me write another one.

She also tells a story about inviting some World War II buffs to come to her home and assemble for her a replica of the gun turret that her main character would have flown in during WWII right in her own living room. They put arial maps on the floor and scrolled them along so she could imagine what he would have seen as he flew by, imagine how he would have felt. It was an extravagance, but one that writing the bestselling Seabsicuit had afforded her. If nothing else it showed her dedication to getting it right, a dedication that surely contributes to how immersive and enjoyable her books are to read.

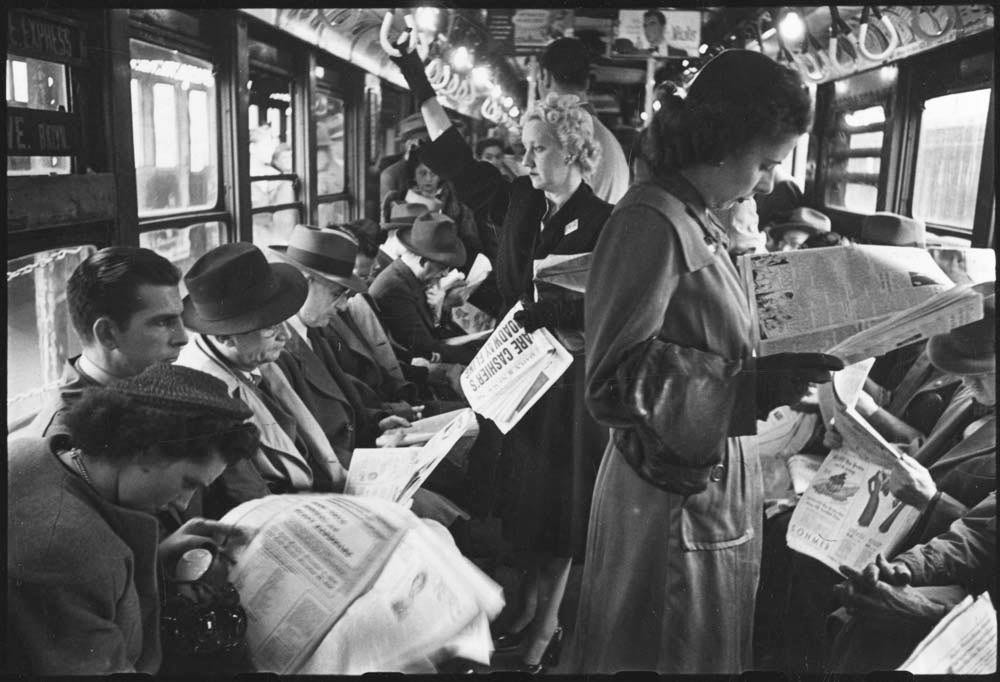

The thing that really stuck with me, though, was how she spent hundreds of hours on the phone with people doing interviews without ever meeting them face to face. As an author and as a journalist, I spend so much time traveling to meet the people I’m writing about, and getting them to sit down with me. There’s an assumption that being together creates intimacy, brings you closer, and allows you to get someone to open up to you. But the opposite might be true. Hylton interviews Terri Gross from the NPR program Fresh Air, who conducts almost all of her interviews by phone. “I find it to be oddly distracting when the person is sitting across from me,” she said to Hylton in the piece. “It’s much easier to ask somebody a challenging question, or a difficult question, if you’re not looking the person in the eye.” Hillenbrand concurred. She says that interviewing Louie Zamperini, who was then in his 90s, by telephone allowed her to imagine him as he was in the stories he was telling, as he was in the story she would write about him. “He became a 17-year-old runner for me, or a 26-year-old bombardier,” she said. “I wasn’t looking at an old man.”

I’ve been spending a lot of time on the phone lately doing interviews for a project I’m working on. Interviews that I originally wanted to do face to face. But I’ve found that the phone interviews have stretched on for hours when they may have been much shorter if I was trying to squeeze myself into the middle of someone’s busy schedule. And I’ve found that the conversations have been emotional in ways I couldn’t imagine them being face to face. I often forget that it isn’t just me that’s trapped down here in this basement. We are all trapped at home, going through the same predicament. We are all desperate to talk out loud to someone, to have some back and forth that isn’t typed out with our fingers and thumbs. And doing these interviews has brought me back to this place I was in when I was trying oh so hard to be a good writer. I remember writing this piece about the poker player Jason Mercier years ago, and wanting so badly for it to be a good piece of writing even though I was writing about something that had already happened and that I wasn’t there for. I knew I’d only likely have one source for the story, Jason himself. And I remember back then having Laura Hillenbrand much fresher in my mind and asking him if we could schedule a series of long phone calls to do the interview, then using the time I had with him to make him describe for me everything that happened in painstaking detail. “What were you thinking when you saw that?” “What did it feel like when you picked it up?” “How far away from you was the clock you were looking at?” I’m sure he was annoyed at first, but he eventually got into it when he realized what I was up to. Later, after the piece came out, I heard him on a podcast telling an interviewer how impressed he was that I was able to ask the right questions and write the story as if I was "looking over his shoulder the entire time.” I remember how proud I was of that story and that compliment.

I’ve drifted far from that writer I was back then I think. I’ve done some stories that were the polar opposite of that kind of story - where I spend little to no time speaking to the people I’m writing about and instead writing all about my own personal experience reporting on them. I don’t know that it is any better or worse - just different. But I know that when I did it the other way, it was noticed, and that mattered to me. And I know that I can feel myself becoming that kind of writer again out of necessity, and it’s good to know that I don’t get to use the lockdown as an excuse for bad writing, and might even get to credit it for some good writing. But now I’m getting ahead of myself.

Right before the quarantine really set in we were shopping for a house to buy, having finally decided to stay in Nyack for good. That search is of course now on hold, and it’s incredibly frustrating to have resolved ourselves to make this big change in our life, only to have it snatched away indefinitely. So that may be a major contributing factor to my bad feelings about my family’s dwelling, and in particular this basement where I’m now forced to do my work, with no diner to escape to when the going gets tough. But like Laura Hillenbrand, I think the best writing comes when we can get out of our own head, out of our own present state of mind, and out of our own present surroundings even, and fully put ourselves in the location of our stories. Perhaps being forced to write in a place I desperately want to escape can help me get to that place quicker and easier. Perhaps writing (and all that goes along with that, like research and reading and reporting and interviewing) can be the thing that takes me out of the basement room, out of the quarantine, out of the pandemic, and into a whole other place and time. Perhaps that’s true not only for me, but for lots of writers. I have no doubt that somewhere in America someone is writing our next great American novel, someone is writing our next canonical work. Something good might come of this bullshit. Something good just has to.

Laura Hillenbrand announced last month that she had contracted COVID-19. She has struggled to breathe. At one point she tried to go for a walk and after about fifty yards had to sit in a ditch for a half hour trying to regain her breath before she could make it back home. She has been alarmed by how many people seem to not be taking the virus seriously, gathering in groups, visiting friends. She points out in her post that she’s not elderly, she has no respiratory or immune issues, and she already spends nearly all of her time at home, yet she still contracted the virus. “Our only weapon is isolation,” she says, “and it only works if we all do it.”

States around the country are choosing to open back up for business, and people are headed back to work. I have family and friends back in Arkansas who are back at work already, their kids back in daycare. It’s understandable that we all desperately want out of our homes, that we all desperately want life to go back to normal. All of us want that. But one thing that strikes me is that a lot of Americans think that the measures we are taking are merely to protect ourselves, and that those of us who aren’t afraid of getting it can afford to take the risk. But the reality is that these measures aren’t about protecting ourselves from getting it as much as they are about protecting others from getting it from us. It’s an important distinction, one that requires of each of us a sense of selflessness and solidarity. We act like we all already have the virus so we can keep from spreading it to those who might be most vulnerable - a group that Laura Hillenbrand rightly points out is much more expansive than we might think. We stay home not to protect ourselves, but to save other people’s lives.

I can’t help but worry that what’s happening in Arkansas and other places is just going to have the opposite effect it’s intended to - rather than speed our return to normal, reopening so soon will just make this whole thing last longer and longer. That means me and everyone else climbing our basement walls will have our agony prolonged. But more importantly it also means that thousands of people will literally die when they didn’t need to.

Now is a good time to think about Laura and what wonders being at home can provide. For those of us lucky enough to be quarantined with family and loved ones, this is a time to grow closer to one another, to appreciate each other more. This is a time to talk to old friends on the phone, the ones we’ve thought of so often but haven’t had time to do more than text or post on their Facebook wall or like their photos to let them know we’re still alive and thinking of them. This is a time to pull the book off the shelf we’ve been meaning to read, or sit down and write the thing we’ve been meaning to write. And yes, we are all struggling financially, and that’s a serious concern. But rather than demand we be allowed to go back to work, we should demand that our government take our economic distress seriously and provide for us as we all pitch in to do the right thing and save each other’s lives by staying home. If we do all that, we can make sure that something good comes out of all of this bullshit, all of this death and devestation, all of this surreal insanity. The good may not in the end outweigh the bad, but I’d like to know the good at least put up a fight.

With love and solidarity,