Regnat populus. The people rule.

A group of American soldiers are huddled together in an old garage, each of them armed with a 12-gauge shotgun. As they load the weapons, one of the GI’s takes a peek out of the garage window. Next door to the garage is an office building, folks lined up outside the door. Someone leaves the office building carrying a box. The soldiers get excited. This is it. One racks a shell into the chamber of his shotgun.

Do we stop him? he wonders.

The man with the box keeps walking. As he nears the garage where the soldiers are holed up they get a better look at what he’s carrying.

Is it the ballot box?

It isn't the ballot box. Just a box of files. The soldiers breathe a sigh of relief and relax against the walls of the garage. The year is 1946. These soldiers aren’t on active duty. They are veterans of World War II, recently home from combat. This garage where they are hiding isn’t in a foreign country. It’s in Hot Springs, Arkansas. These young veterans are watching a polling place to make sure nobody tries to steal the ballot box or tamper with it in any way. Among the group of soldiers are candidates for local office. They had good reason to be armed and hiding. Their opponents were armed and hiding nearby as well. This wasn’t a normal election, but it was the fairest election in Garland County in over twenty years.

In 1946 the Mayor of Hot Springs was a man named Leo McLaughlin; a Democrat, naturally, who was often referred to as “Mayor for Life.” He was first elected in 1927 on a promise that he would open up Hot Springs to wide-open casino gambling. He made good on that promise, and ushered in an era that came to define Hot Springs and put it on the map as a worldwide tourist destination. He was able to keep gambling open in Hot Springs, despite the fact that it was illegal under all local, state and federal laws, because of his firm control over the entire local political establishment. The judges, tax collectors, law enforcement officers, prosecuting attorneys, they all were part of what was known as the “Little Combination.” They all did what they had to do to make sure that gamblers weren’t prosecuted and that the gambling industry contributed to the general welfare of the town. It was an arrangement that kept most everyone in Hot Springs happy. The casino money paved roads, built a convention center, an airport, public pools and parks. The city thrived, so the locals supported gambling and McLaughlin’s machine. But that popularity wasn’t enough to insure the safety of the casino business. It required every single arm of the local government acting in concert to keep it going. A single defection, a single minor office changes hands, and the whole thing could come tumbling down. So McLaughlin rigged all of the elections in Hot Springs, buying up many books of poll tax receipts and signing other people's names to them, casting their votes on their behalf. Every election McLaughlin would dispatch gamblers and gangsters to drive around town, pick up underlings and take them to polling places to cast thousands and thousands of fake ballots. Even though the people of Hot Springs seemed content to return the McLaughlin machine to power year after year, like any good gambler McLaughlin didn’t want to leave anything to chance.

In 1946 a group of young GI’s who had returned from the war decided they wanted an opportunity to participate in local government and begin to build their own political careers. Some of them opposed gambling and the political corruption it engendered. Others supported McLaughlin and gambling in Hot Springs, but simply felt it was their turn to take the wheel. They joined forces and ran as a slate of candidates for nearly every local and county office that year in what came to be known as the “GI Revolt.” They announced their candidacies in dramatic fashion with a propaganda maneuver they learned in the war: they dropped leaflets all over the county from an airplane.

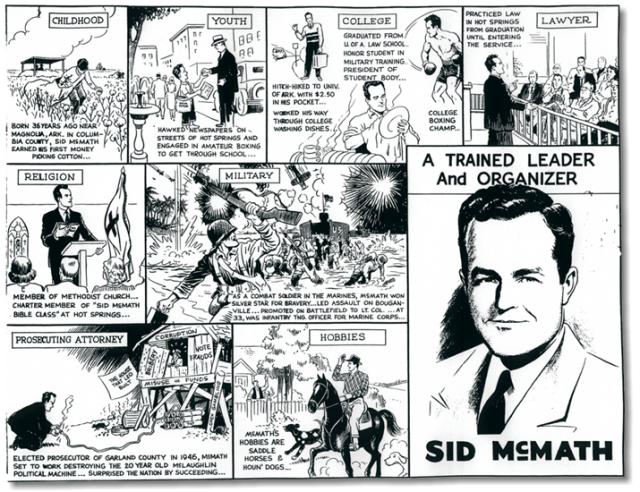

At their first campaign event, the candidates stood together on stage dressed in their military uniforms. The leader of the group, a young and charismatic former Marine Lieutenant Colonel named Sid McMath, addressed the crowd of 800 people and compared Leo McLaughlin to Adolf Hitler. As the rally went on, outside in the parking lot members of the Hot Springs Police Department were checking in on the event at Leo’s request. They brought with them boxes of roofing tacks, which they scattered throughout the parking lot. After the event’s conclusion, the young candidates rolled up their sleeves and stayed behind until they had changed every single voter’s flat tires.

I changed my voter registration from New York to Arkansas in order to vote in a special election last month over a proposed school millage worth over $50 million to the Hot Springs School District. Though I'm new in town, and a temporary resident, my parents and I attended these schools and this year my children are attending them as well. I’m well aware of what the school district is facing and what the money would go towards. I own property in the area and so I already pay the taxes that would be affected by the millage increase. I had a strong opinion on the election and was invested in the outcome, so I voted. The millage passed by only 40 votes, so I feel like my vote really counted.

Now I find myself registered to vote in Hot Springs during a general election. My vote for President will be just as insignificant here, a state that Trump should win by a huge margin, as it would have been in New York, where Clinton stands to win by an equally large margin. But there are local candidates up for election, too. I don’t know the candidates and I’m only just learning about the issues. Yet I have an opportunity to vote, and unlike in the Presidential or statewide races, my vote could matter a great deal.

Fortunately I had the opportunity to attend a real live debate between the two candidates running for City Board of Directors for the district where I live. The debate was held at a nearby nonprofit arts center. It was broadcast live over our local community radio station. There were nearly 30 people in attendance. I overheard a couple of people in the audience complain that so few people had bothered to show up, but I was blown away by how many did. It’s a rare thing these days to see this kind of participation in politics, this much enthusiasm at what is literally the smallest level of politics. The issues at the neighborhood level aren’t sensational. There’s no talk of ISIS killing us while we sleep or ripping babies from the womb (at least, not in our district. I can’t speak to what goes on over in District 3). It’s all parking spots and historical landmarking. But surprisingly those kind of unsexy issues are the ones individual voters can find themselves getting animated about very quickly. Because those are the issues that impact their day to day lives in tangible, understandable ways. And those are the issues where the various solutions being offered all seem to them to be at least possible, so the debate over their efficacy has more resonance than a debate over policy proposals at a federal level that feels pie in the sky.

The two candidates traded differing visions for the neighborhood. There was some debate about the fact that our neighborhood is a recipient of Community Development Block Grants due to its designation as “blighted.” But other than that, it felt like more of a community forum than a back and forth debate. Members of the audience got up and spoke about their own ideas for what the area needed, and the candidates listened to them. People were respectful to one another. Though the talk was on grants and parking spots and other municipal minutiae, nobody grew bored. People were streaming the debate from their phones over Facebook Live, where many more residents of District One were watching online. After it was all over, we got into our cars and drove away; our minds made up, our tires unpunctured.

If the tack incident didn’t tell the young veteran candidates what they were in for, they soon learned just what lengths McLaughlin’s machine would go to in order to stay in power. The GI’s knew they couldn’t win if McLaughlin continued to buy up blocks of poll tax receipts. They decided to file a lawsuit against him over the practice. In the days before the hearing, one of their lawyers was held up by a gunman who demanded he turn over his briefcase full of affidavits. The gunman didn’t even bother to wear a mask. He was Ed Spears, a local bookie, who also served as McLaughlin’s Deputy Assessor. Spears readily admitted to the robbery and was convicted, but the damage to the case was done. A number of the witnesses that the GI’s had taken affidavits for ended up recanting their statements and became witnesses for the defense.

In the weeks leading up to the primary, members of the GI ticket were encouraged to drop out of the race with bribes, or offered positions to come over and serve on the McLaughlin ticket. When it was clear none of them would accept, the bribes turned to threats. One member of the GI ticket, Q. Byrum Hurst, received phone calls threatening to hurt his wife and infant daughter. McMath and some of the other soldiers at one point went right into McLaughlin’s office and confronted him. They told him that if he wanted any more gunplay, “we have some people on our side who have some recent experience in that kind of activity...We’ll start at the top.” On the day of the primary, teams of GI’s posted up at polling places with shotguns and cameras, prepared for the worst.

There was no violence that day, but the heightened pitch of the campaign likely kept voters at home. With a low turnout, the GI’s lost every primary race but one - Sid McMath was nominated for Prosecuting Attorney over incumbent Curtis Ridgeway in a close contest of 3,900 votes to 3,375. While the GI’s were unable to overcome the McLaughlin machine’s ballot box stuffing in Garland County, McMath’s race extended beyond Garland and into Montgomery County. McMath later claimed his success in that election was due to the phone lines being mysteriously cut between Mt. Ida in Montgomery County and Hot Springs, which prevented McLaughlin from communicating with anyone in that county about the vote until the polls were already closed. His inability to tamper with the Montgomery County vote put McMath over the top.

The night before the District One debate in Hot Springs I watched the final Presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump on television. Like the first two Presidential debates it was completely bananas. It's hard to rank the things Trump has said over the last 18 months in order of outrageousness, but this debate offered a strong candidate for the top of the list: he refused to say that he’d accept the results of the election if he lost. The following week he and his surrogates and supporters would push the narrative that voter fraud was rampant across America and that the election was likely rigged against him, inoculating his supporters for his coming defeat.

The reason this argument is so tantalizing to his supporters even without any evidence that it is true is that most of his supporters can’t fathom that they are among the minority in America. They believe that America is their country, that their values are the the only true American values, that the majority of people agree with them and the ones who don’t are part of the fringe. When a poll or an election proves this not to be the case, it’s difficult for them to make sense of it. There must be a conspiracy! Our voices have been suppressed!

Living here in Arkansas I can understand how so many people delude themselves into just such a fantasy. As I stood in line for over an hour to vote during early voting here, I was surrounded on all sides by aging white people, complainers and conspiracy theorists all, who were vibrating with excitement to vote for Donald Trump while at the same time on edge anticipating the inevitable glitch in their voting machine or manipulation by shifty poll volunteers that would cancel out their vote. A friend of mine in Chicago who supports Donald Trump tells me he lies to his co workers and tells them he is for Hillary for fear of being ostracized. In Arkansas the opposite dynamic is at play. Standing in line to vote, I was actually nervous a nosy neighbor might ask me who I was there to vote for, and I didn’t want to have to defend my write-in vote for Rasheed Wallace to a complete stranger. But the fact is, around these parts, the Trump folks really think they are the mainstream of American culture, because everywhere they look they are surrounded by other people who think exactly like them. Whether on their Facebook feeds or IRL on the streets of their town, they actually are the mainstream. So who is Anderson Cooper to tell them any different?

This illusion, that the whole country thinks just like us, is exacerbated by the segregation and isolation of American life. And Donald Trump's assertion that our democracy doesn't work, that the majority isn't really the majority, that the only way the other side could win is by cheating, gives his supporters the comfort of never having to question how out of step they actually are with the rest of America. He absolves them of ever needing to reckon with the fact that the country they love and the system of government they celebrate as the best in the world is the same one that rejects them and their values. It's maybe his worst injustice, allowing that kind of fraud to continue, and never giving his people their dark night of the soul they so desperately need if they're ever to repent.

In the 1946 Democratic primary, an actual rigged election, the GI Revolt was crushed in defeat. But the GI’s didn’t lay down and surrender. They continued to organize, they registered new voters through a concerted poll tax campaign, they filed more voter fraud lawsuits, and they entered the general election as independents. They never stopped campaigning against the McLaughlin machine. They appealed to the people of Garland County that even though they may support the largess that gambling brings to the community, the violations of their civil rights and their franchise were too heavy a price to pay. They had defeated fascists in Europe so that people could vote in fair democratic elections. No American should surrender that right at any price, they argued. And the argument worked. In the general election of 1946 the GI’s would unseat every member of the McLaughlin machine with the highest voter turnout in the history of the county. Sid McMath would go on to become governor of Arkansas. Leo McLaughlin would be indicted. Ballot-stuffing would end in Hot Springs and power would change hands through fair elections from that day on.

Gambling, however, remained. The casinos stayed open under the GI regime, and outlasted them, too. Long after most of the GI's had moved on from government, long after McMath's tenure as governor, for the next twenty years, gambling in Hot Springs grew bigger than Leo McLaughlin could have ever imagined. Nor could Leo McLaughlin ever have imagined that the people of Hot Springs were capable of supporting what his machine had done for the city while at the same time rejecting the manner in which they had done it. Because he rigged the elections, disenfranchising the people from their government, he planted the seeds for his own demise. In the end the argument that he rigged the elections was the one argument the GI's had against him that worked. Without that criticism, and in an open and fair election, perhaps McLaughlin truly could have been mayor for life. Q. Byrum Hurst, who served in Arkansas politics for the next 25 years, was later asked if the members of the GI Revolt had lost some of their integrity by continuing McLaughlin's practice of wide-open illegal gambling after they came to power. “Yes, some of us did,” Hurst said. “The people demanded it.”

Vote Quimby,

David

P.S.

I'm leaving town this week to go to LA to accept an award I won for this piece I wrote earlier this year about the Kentucky Derby. I left for Las Vegas to report on this story literally two days after my son Harry was born, leaving Katie alone with two kids and a newborn for a week. Now I'm leaving her alone with the kids again to go pick up the award. Life is full of small ironies. Anyway it's not really a newsletter without some personal bragging and I've fallen behind in that department.

P.P.S.

If you read Letters From Hot Springs on the web and you enjoy them, please subscribe so that you'll get them in your emails. It helps me out when you do, and you'll never miss one. You can subscribe by clicking here. Thanks.