Bobby Fischer won his first U.S. championship at the age of fourteen, the youngest to ever win that title. At fifteen he was the youngest player to ever achieve the rank of grandmaster. In January of 1964, at the age of twenty, Bobby won his sixth U.S. championship with an astounding undefeated score of 11-0, a record that stands to this day. Soon after winning that title, Fischer embarked on a tour of the United States.

It seems natural, reading this today in 2017 and knowing all we know about Bobby Fischer and his place in history, that Fischer would do something like this. After all, he was an American celebrity. More than just a chess champion, he was a World Champion, the only American to ever accomplish that feat, and one who defeated the mighty Soviet Union during the Cold War and at a time when they dominated the chess world. He was on the covers of magazines. He was interviewed on television talk shows. He was a household name, his exploits printed on the front page above the fold. Even though Bobby Fischer was the only chess player most Americans had ever heard of, the point here is that most Americans had heard of him.

In 1964 when Bobby set out on his tour of America none of those things were true. Bobby Fischer was already a remarkable chess player, but most Americans knew nothing of him. Most Americans didn't care about chess at all. In 1964 most people who played chess at a top level lived in New York City. There were fewer than eight thousand members of the US Chess Federation, compared with over eighty thousand today. Most chess was played in local clubs among largely untalented recreational players. Fischer requested $250 for each appearance. Most clubs had to cobble that money together by passing the hat among their members. They put Fischer up on their sofas. They ferried him from city to city in their backseats like a secret society, a brotherhood devoted to an ancient board game delivering their prophet to one another so they each may touch the hem of his garment. So in awe of him the American chess faithful were.

This was the world as it was when word was spreading across Hot Springs, Arkansas that Bobby Fischer was on his way to town.

***

My mother and father used to argue about which one of them taught me to play chess. I tend to think it was my father but it really doesn't matter because whichever of them it was, the only thing they taught me was the way the pieces moved on the board. I learned to actually play chess from my friend Josh in a pizza joint on Park Avenue around 1992. He had demolished me, along with the rest of Hot Springs High School, in our school chess tournament. I remember being so impressed by him. The way he touched his pieces. The way he would tap the top of each piece with his palm when talking about it. The way he hit the button of his clock with the piece he just captured from the board. And oh how I coveted his clock! His vinyl chess board! His weighted wooden pieces! And all of this he carried in a special bag he kept slung around his shoulder. Oh how I wanted to be as good at anything as he was at this silly game.

But while I was envious of Josh's chess equipment and his prowess over the board, I was equally enthralled with the hidden mysteries of this simple game my parents had taught me as a child. Clearly there was much more to it than just the movement of the pieces, the rules of the game. There were players in that tournament who moved the pieces as if they were doing it from memory, as if everything I was doing on the board they were ready for. It was like they had played this game with me already in the future or in some kind of parallel universe or dream state. What other explanation could there be? Whatever the secret was, I needed to know it.

Josh agreed to share his secrets with me at Pizzariffic one Saturday afternoon. He taught me about controlling the center of the board, never putting a knight on the rim (it's dim!), capturing towards the center, not moving the same piece twice in the first ten moves, forks, skewers, pawn chains and opposition. It was a lot to take in one afternoon. But I soaked it all up. I sensed the lid of the treasure chest was giving way, and could see the glimmer of what was inside. I wanted more. Josh gave me a stack of old issues of Chess Life magazine and an old broken set and board of his. The next week I left with my father for the summer to go build a Chili's in Bumfuck, North Carolina, bundle of Chess Life magazines in tow.

I spent that summer doing construction with my father and living in a Motel 6 by the highway. It was miserable and lonely. The work was hard. The weather was humid. The money was a joke. Our only companionship came from the painter on the job who was also staying at our hotel who would sometimes invite us to the local bar to play darts. We did that a few times but one night there was a big drunken fistfight with some bikers so we kept away after that. Mostly we sat in the hotel room and ate baloney sandwiches out of an ice chest to save money. My dad would read novels about Vietnam while I sat at the desk by the window and played games out of the Chess Life magazines.

"I don't understand how you can play chess against yourself," he'd say. "Don't you always lose?"

Sam Spikes was a successful insurance salesman in Little Rock, Arkansas. He was enthusiastic about chess, though he wasn't terribly good at it. He heard that Fischer was planning a tour after winning the U.S. Championship again and he wrote him to ask him to consider including Little Rock. He volunteered to put up the $250 personally and to host Fischer in his immaculate home. He promised Fishcer his own bedroom, bathroom, and plenty of privacy for as long as he'd like to stay. Fischer responded that he'd love to visit Little Rock. He planned his visit to coincide with the Arkansas State Chess Championships.

Fischer arrived in Arkansas on the last day of the tournament, March 29th, 1964. As part of his deal he gave a lecture to the assembled players at the Albert Pike Hotel. He analyzed a game he lost to World Champion Mikahil Tal. "I thought I was better than Tal," Fischer said, "but it was hard to convince anyone else after he had beaten me four times." It was a joke. A funny, self deprecating joke. This wasn't the Bobby Fischer people had heard about. Folks who had heard of Fischer before were bracing themselves for a rude, arrogant, eccentric boy who blew up at the drop of a hat. This young man was charming and witty.

Bobby Fischer started playing chess at the age of six and dropped out of high school at sixteen to pursue chess full time. His father had left the United States when he was very young and his mother raised him and his sister on her own. She was Jewish and she came to the United States before the war to flee the Nazis. She was educated but spent her time here working odd jobs. When Bobby was born, his mother was homeless.

Fischer spent most of his time by himself studying chess. At first his mother distressed over his obsession. She thought it was unhealthy for him to spend so little time with other children. She came to understand his devotion to chess was ingrained in him, so she surrendered to it and let it take over. She worked extra jobs and borrowed money from friends so that he could enter tournaments. It was worth it to her, because it was the only time her young son seemed at all happy. And happy in those instances was still a stretch, since chess was emotionally and intellectually taxing on the child.

Fischer's isolation from the world may have contributed to his strange and off-putting behavior once he became a player of renown. But in 1964 when he went on the road, he was practicing reeling those traits in. It wasn't too hard. Wherever he went, though he was among strangers, he was still among friends. The players that came to play against him and take him in to their homes and drive him from city to city were his adoring fans. He didn't need to prove anything to them. They already believed that he was the best. They, like himself, wanted badly for him to compete and win the World Championship for the United States. Around these people Bobby Fischer could be at ease.

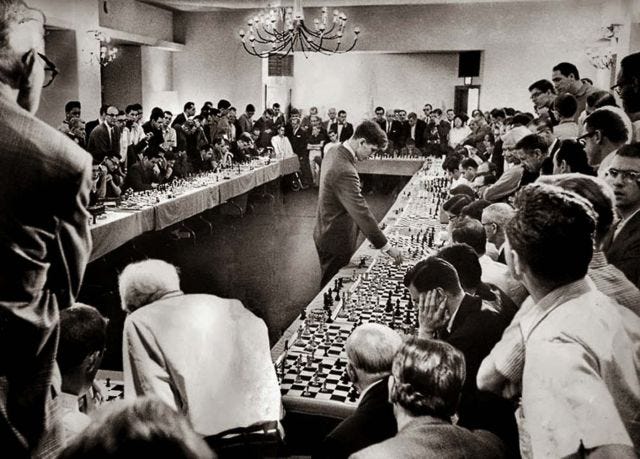

After his lecture in Little Rock Fischer performed a simultaneous exhibition, or "simul," in which he played thirty six players at one time. Each player payed $5 to play, and Bobby got to play white on every board. Though he was notoriously competitive, taking glee in watching his opponents "psychologically break inside" when he won and storming out of rooms in tears when he lost, during this tour he was friendly and easy-going. When Bobby lost games from time to time, he'd congratulate his opponents. When he lost to a fifteen year old in New Orleans who had just recently learned the game, he expressed surprise and delight. When he played weaker players during simuls, he was known to "give chances," choose weaker moves in order to allow his opponents to catch up. When he played a fourteen year old girl in the simul in Little Rock, he let her play white.

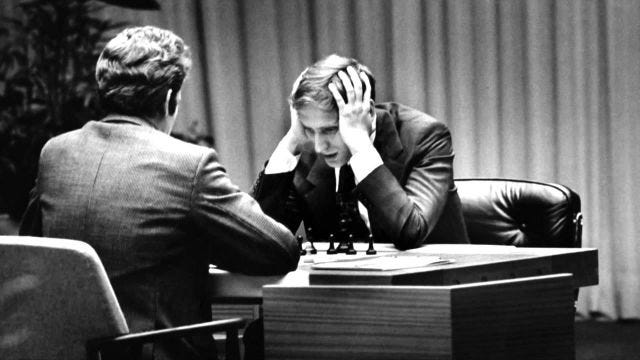

Bobby Fischer won 35 of the 36 games in Little Rock. It was down to the final board, where he was thirty moves deep into a game with an FBI agent from Hot Springs named Orval Allbritton. Once Fischer finished the other games, which he played standing up and walking casually from board to board, he drug a chair over to Orval's table and sat down across from him to study the position. "When you're the last guy and he pulls that chair up," Orval told me while recalling the game this week, "you've got yourself a situation."

After being down a pawn to Orval, who at the time was rated a very respectable 1787, Fischer came back and went up a pawn of his own. Soon after, Orval resigned the game. The rest of the players, who by now were standing around the last board like a peanut gallery, moaned in disapproval. They all started in on Orval about how he should have done this or that, trying to tell him how he could have won. Orval tried to keep his composure. Fischer spoke up in his defense. "I would have won," Fischer assured the crowd. "I had a winning position. He saw it." It was a very weird combination of arrogance and respect, but Orval was thankful for it.

That night Orval joined Sam Spikes and Bobby Fischer for dinner in the dining room of the Albert Pike Hotel. "If I'd have beat you," Orval joked, "I would have bought you supper." Fischer pulled out his pocket chess set from inside his suit jacket. "Let me see if I can find a way you could have won, then!" The two of them worked on the game to see where Orval went wrong. They couldn't find a win. "Oh well, I'll just pay for my own supper," Fischer said.

Bobby Fischer gave interviews to a number of local papers during his tour; interviews that show a glimpse of the polarizing public figure that Bobby would soon grow into. He bragged about his chess skills and boasted that he'd soon win the World Championship. He called women stupid and said they shouldn't play chess. He came off as cocky and immature and left a bad impression on journalists. This was in contrast to the positive impression he left on the thousands of chess players he met on tour. Almost every account of that tour, the first look that most chess players in America had of their national champion and one day standard bearer, is overwhelmingly positive and complimentary of Fischer's manners and charm. It seems that there were two Bobby Fischers at war inside of him. The one that lost the war was most comfortable among friends who understood him and, more importantly, understood his obsession. That Bobby Fischer stood no chance in that war. He was up against a true monster.

"I'm not as soft or as generous a person as I would be if the world hadn't changed me," Fischer told an interviewer, showing a remarkable self awareness even at that young age. "I don't keep any close friends. I don't keep any secrets. I don't need friends."

"I live alone and like it. Most of my income comes from tournament chess and exhibitions like these. I don't take advice from people. Everyone has ulterior motives. Besides, nobody knows as much about my problems - or cares - as I do."

***

Because the World Championship could only be contested every three years, Bobby Fischer was forced to wait for his shot at his lifelong goal. "I'm just marking time," he complained. He moved to Pasadena, California where he fell in with the Worldwide Church of God, an evangelical Christian doomsday cult. He spent his days in California riding aimlessly on the bus between L.A. and Pasadena, working on chess puzzles and reading the Bible and Nazi propaganda. He developed a hatred of Jews and communists. It's likely this stemmed from his complex relationship with his mother, who was both Jewish and an avowed communist, for being absent through much of his childhood because of her work and her dedication to anti-war and anti-capitalist causes.

The years between 1964 and Fischer finally getting his shot at the World Championship in 1972 saw Fischer play some of the most inspired chess the world has ever seen. He achieved the rating of 2785, the highest of any player up to that point. The USSR had built a stable of incredibly strong chess grandmasters, and the government subsidized their study and play around the clock. During this period of time, Fischer demolished every Soviet player he had the opportunity to play. He destroyed the top Soviet grandmaster Taimanov 6-0 in one tournament. The USSR grew nervous that Fischer could unseat them from the top of the chess world and win the World Championship. They conspired to keep him from qualifying for years through collusion and evasion and any other dodgy tactic they could come up with. When they could hold him off no more, their entire country helped their champion, the undefeated Boris Spassky, prepare for the match in 1972. Bobby Fischer prepared for the match alone on the bus with his pocket chess set.

After a dramatic and grueling match that spanned three months, Fischer won the World Championship 12.5 to 8.5. He was the toast of American popular culture, on the cover of magazines and interviewed on every talk show. He invigorated an interest in chess in the United States. He was offered millions of dollars in commercial endorsement deals, all of which he turned down. He went on the Johnny Carson show, where Carson asked him how he felt after finally capturing the thing he spent his entire life chasing, the World Championship. Fischer said "I feel like something's been taken from me."

And then he disappeared for the next twenty years.

Fischer resurfaced in 1992 while I was staying in a Motel 6 with my dad working construction. He agreed to play a rematch with Boris Spassky for five million dollars in Yugoslavia. Because the United States had ordered Americans not to do business with Yugoslavia over the Bosnian conflict, a letter was sent to him by the Justice Department threatening him with arrest if he went through with the match. Fischer read the letter at the press conference before the match and then spit on it. He spent nine months in jail.

Fischer died in 2008 in Iceland where he had been living as a total recluse. When he did occasionally surface in the final years of his life, usually on the radio, he went on anti-semetic rants about Jews or applauded the September 11th attacks. He had few friends to tether him to reality. He didn't even have chess to keep him company, having abandoned the game long before he died, swearing it off as "boring." His incredible brain was completely broken and finally useless.

In Fischer's obituary in the New York Times, Grandmaster Bruce Pandolfini said “After 1972, we lost so many great pieces of art, hundreds of masterpieces he would have created if he had stayed a sane being. We feel the great loss. All chess players do.”

***

The day after the simul in Little Rock Bobby Fischer decided to spend the day in Hot Springs to take in the sights of the resort and to give Orval one more bite at the apple. He called down to Orval to let him know, and Orval spread the word by phone to the few chess players he knew in town. By the time Fischer arrived there were over twenty people gathered in the meeting room at the Freeman Center Apartments to get a look at the young U.S. Chess Champion.

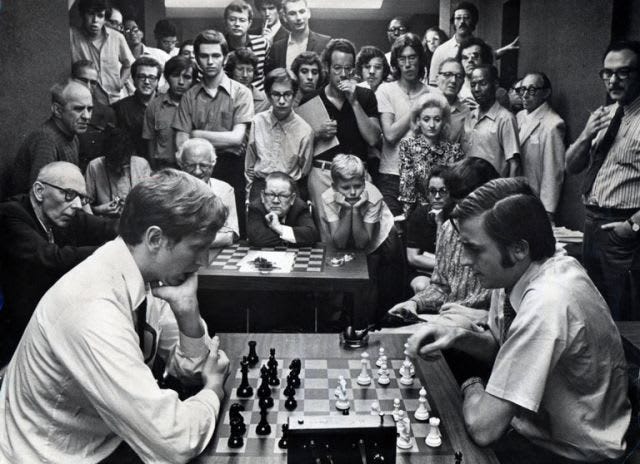

Fischer was not there for a lecture or another exhibition. He had only one purpose that afternoon. He was there to play Orval Allbritton one more time. The two men sat down at the table and, as the crowd looked on, they played a friendly game of chess. Orval played black again, and just as he did the night before he played the French Defense. Just like the night before, Orval lost the game. He was unfazed. He didn't expect to win. He asked Fischer to sign the score sheet, and Fischer obliged. After doing a little sight seeing, Fischer drove back to Little Rock that night, and eventually made his way to Witchita, Kansas for his next exhibition.

Bobby Fischer would visit forty two cities and play over two thousand opponents during this tour, as many as fifty at a time. He would win over ninety four percent of those games, including two hard-fought victories against Orval Allbritton.

I tried to teach my son Gus to play chess when he was three but it just didn't take. He was too young. I tried again at four and he started to pick it up. By five he was playing twice a week in the chess club at P.S. 154. He's now six and he's played in a few tournaments. He's even beaten me a few times straight up. He seems to really love the game, and until he decides he doesn't anymore, I'm elated to play with him.

Despite not being very good at chess, I've held the game close to my heart my entire life. I often wonder why. That isn't to say that chess is not a wonderful game. It is. It's elegant - simple to learn and difficult to master, a brand new puzzle to solve nearly every time you play. It is beautiful, perfectly logical yet rewards creativity and imagination. But chess also is strenuous, and in the heat of a game filled with tension, it can be more stressful than fun.

When I try to retrace my steps to figure out why I love chess so, I always end up back in that Motel 6 in Bumfuck, North Carolina. That summer I spent with my dad busting my ass and eating baloney, wishing I was back in Hot Springs with my friends swimming in the lake and flirting with girls. I learned a lot that summer about my dad, who spent his entire adult life in those hotel rooms on construction jobs all over the country, wishing he was back home with his family. I spent those years wondering where he was, wishing he was home with us, being pissed that he was missing out on our life, that he wasn't around to be my dad. That summer I spent with him on that job I realized all those years he was pissed about the exact same thing. He wasn't off somewhere having his own private life without me. He was all alone. Unlike Bobby Fischer, or perhaps just like Bobby Fischer, he didn't much like it.

Not long after we moved to Arkansas I started taking Gus to a local coffee shop on Monday nights to practice chess. I was worried that he was missing out since he used to play twice a week back in Brooklyn. So we'd go after school and get a snack and play a couple of games with each other, then he'd watch a chess video on the computer. After a few weeks of this, the owner of the coffee shop asked me what I thought about him making Monday night a chess night and opening it up to other players. A few months later and now we have a weekly chess club. Gus has made a few new friends there. He looks forward to going every week so he can see them. I'm grateful for that. It's hard to make friends in a new place.

Today we went to the coffee shop to play chess, and after everything wrapped up Katie came and picked him up to take him swimming. I stayed behind to do some writing until the coffee shop closed. A while later a man walked in. He was wearing a uniform from a local auto body shop. His hands were covered in grease. He had a plug of chewing tobbacco in his lip and was spitting into a styrofoam cup. Under his arm he carried a chess bag. He asked if he was too late for the chess club. I told him he was. He said he had heard about it but could never make it because of work, but today he took off early in hopes of making it on time. I told him I'd play with him, and he smiled.

"I just get tired of playing on the computer," he said. "It's nice to play with an actual human being once and a while."

We played three games over the next few hours in total and beautiful silence.

Without ulterior motives,

David

P.S.

Orval Allbritton is much more than a great chess player and former FBI agent. He is an amateur historian and perhaps the foremost authority on the history of organized crime and gambling in Hot Springs, Arkansas. His research and books have been absolutely essential to me in researching my own book, and he has been so supportive and helpful to me while I've been here working on it. If you'd like to read any of his FIVE BOOKS on crime and Hot Springs, you can order them from the Garland County Historical Society.

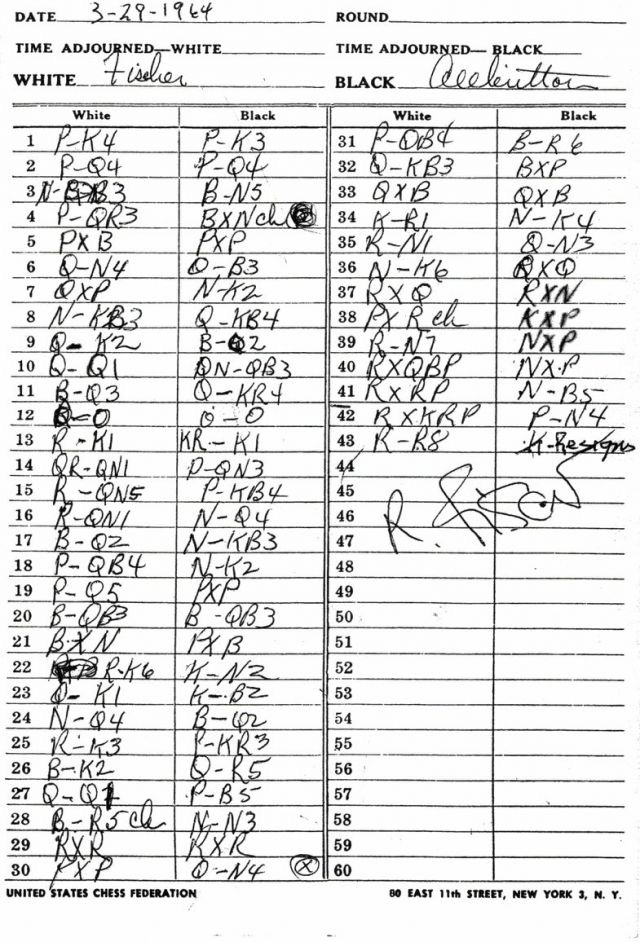

I've included a photo of the actual game Orval played against Bobby Fischer here. I spent a ridiculous amount of time yesterday trying to learn descriptive notation, which they used to record this game back then, and convert the game to the more modern algebraic notation. I also had a chess engine analyze the game. Orval should take comfort knowing that Fischer made more blunders and mistakes in this game. Fischer would likely argue that a computer can't possibly understand the creativity and imagination in his game, and he'd be right. But I wanted to give Orval some pat on the back. Here's the game in algebraic notation if you'd like to take a look at it yourself. Or click here and press play to watch it at Chess.com.

1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. a3 Bxc3+ 5. bxc3 dxe4 6. Qg4 Qf6 7. Qxe4 Ne7 8. Nf3 Qf5 9. Qe2 Bd7 10. Qd1 Nbc6 11. Bd3 Qh5 12. O-O O-O 13. Re1 Rfe8 14. Rb1 b6 15. Rb5 f5 16. Rb1 Nd5 17. Bd2 Nf6 18. c4 Ne7 19. d5 exd5 20. Bc3 Bc6 21. Bxf6 gxf6 22. Re6 Kg7 23. Qe1 Kf7 24. Nd4 Bd7 25. Re3 h6 26. Be2 Qh4 27. Qd1 f4 28. Bh5+ Ng6 29. Rxe8 Rxe8 30. cxd5 Qg5 31. c4 Bh3 32. Qf3 Bxg2 33. Qxg2 Qxh5 34. Kh1 Ne5 35. Rg1 Qg6 36. Ne6 Qxg2+ 37. Rxg2 Rxe6 38. dxe6+ Kxe6 39. Rg7 Nxc4 40. Rxc7 Nxa3 41. Rxa7 Nb5 42. Rh7 f5 43. Rh8