I continue to experiment with the form for these reader’s guides. This week I’ve written up a short synopsis of each chapter, followed by some of the sections of each chapter I highlighted for one reason or another, and some of my thoughts about why those passages (for reasons other than being exceptionally well written) are important.

I do want to point out here at the top, however, that Section IV of Chapter 5, where Barich bets on Raindrop Kid and describes the race, is easily the best passage I’ve read in the book so far and is just absolutely good shit. I loved every word of it and felt myself beaming by the end: “…when I collected my money I could feel the heat in my hands, all through me, and I knew how hot I was going to get.”

Don’t forget that I’m planning to do the livestream on Sunday September 7th in the evening, time and place TBD. So try to finish the book by then.

And don’t forget we are trying to get a discussion going in the chat section of the substack in the meantime, so if you’d like to talk about the book, please join us there! Here’s a link if you’re not sure where I’m talking about.

Chapter 4

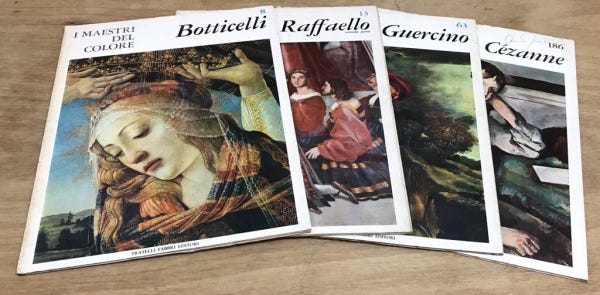

This chapter introduces us to the world of the backstretch, using the metaphor of trainers as Renaissance princes each presiding over their unique principality. Barich highlights the nepotistic nature of the community, comparing it to Medici's Florence, where families often work together. He exposes the corruption within racing, describing how some trainers influence race outcomes through hidden workouts, misleading jockeys, or even illicit use of “joints” (buzzers/batteries) and undetectable drugs. Conversely, he presents Bobby Martin as a top trainer, whose success stems from his expertise in conditioning horses and his strategic mastery of the claiming game (a system of buying and selling horses for a set price). The chapter also connects Renaissance artists' belief in art's dominance over nature to the human desire for control over unpredictable animals. The chapter closes by detailing Barich's own evolving understanding of handicapping, including the “Bandit Syndrome” (horses shipped to win against weaker competition).

“Art is more powerful than nature” (pg 75)

When Barich comes across a carved owl in the grandstand meant to deter birds from building nests, he reflects - once again - on the Renaissance idea that man can conquer nature and impose order on it. He discusses the artists Titian and Vasari and their desire to master and accelerate the processes of nature and to essentially industrialize the production of art. Here we see an object of art created by humans to impose order on the grandstand at the track, yet the birds continue to build their nests anyway. It feels as if Barich prefers this - nature ignoring human innovation. Perhaps this is more of the “American dilemma” he mentioned at the close of Chapter 3, when the playmate said she liked to watch the movies before reading the books - the valuation of illusion over substance. “What can be touched.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to American Gambler to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.